17 Sep 2017

The clan in Shona chiefdoms

The core of each of the Shona chiefdoms or principalities is a clan. This is a group of agnatically related kinsmen and kinswomen who trace their descent from a common founding father, a sikarudzi (creator of the tribe). The chief is the member of this lineage who has succeeded to the position of the founding father, who rules with his approval, and who cares for his descendants. The lineage has its territory of which its members are the varidzi (owners).

Their common ownership is a bequest from the founder to his descendants. In the past, title to legitimate occupation was conferred by the Rozvi to the chiefs subject to them by virtue of their conquest and hegemony. Nowadays chiefdoms occupy land in accordance with the provisions of the Land Acts of the government.

The chief is the senior member of the clan, in status, if not in age. He inherits the traditional title of his chieftainship. Thus, for example, the names Mangwende, Makoni and Mutasa, chiefs respectively of the Nhowe, Hungwe and Manyika peoples, are hereditary titles. They date back at least three centuries as we know from Portuguese records.

The name of the varidzi vevhu (owners of the soil) is usually also the name of the territory in which they live. Thus the Hungwe under Makoni live in MaHungwe, the Manyika under Mutasa live in Manyika, the Mbire under Svosve live in Mbire, the Shawasha under Chinamhora in ChiShawasha, the Njanja in ZviNjanja, the Pfungwe under chief Chitsungo in Pfungwe, the Nhohwe under Mangwende in Nhohwe.

Each member of the clan inherits his totem (mutupo), its principal praise name (chidawo), and its set of praises (nhetembo dzerudzi). These provide both men and women with an important part of their identity, and outsiders with ritual means to show them proper respect.

Clansmen and women refer to themselves by their totem. Thus the Shawasha says of himself, "Ndiri Soko" (I am a Soko viz, a member of the group that is identified with the baboon and monkey, and which treats them as taboo). They use their principal praise name or names in addition if they need to differentiate themselves and their group from others who have the same totem, but different principal praise names.

For example, "Ndiri Soko Murehwa" (I am a Soko with the praise name Murehwa, viz. One spoken about and therefore famous) These groups which have totems in common with others, but different praise names, are normally referred to as sub-clans.

The totem, being sacred to clansmen and women, provides them with an oath, usually accompanied by the words baba (father) or sekuru (grandfather), for example, "Nababa wangu Soko!" (by my father Soko). It also supplies the imagery and a good deal of the content of the clan praises.

The members of the clan share a common mythological and historical account of their beginnings as a clan or sub-clan. A good many of their traditions, and of the clan praises as well, deal with the names and burial places of deceased ancestors. These burial places, the places where the clan dwelt in the past and left its dead, remain sacred, even though they lie outside the present clan territory. The graves of more recent ancestors will usually lie within the clan territory, and are also mentioned in clan praises.

The world of the ancestors is referred to as Pasi (the ground, the world below). Pasi connotes at least those ancestors whom the people remember, and with whom they are in effective contact. The fact that the founding father has left his descendants their land, and that he and other ancestors lie buried in it, constitutes a very real bond between the clan and its territory. A man in his own country is called mwana wevhu (child of the soil), and this name distinguishes him from those whose links with the land are not so close.

The founding fathers and the other ancestors live on with their descendants in the same land, and communicate with them through spirit possession, dreams, and other types of visitation, such as sickness, which require the interpretation of a diviner. Communication is made according to the degree of the relationship and the seniority of the ancestor.

The ancestors who are related to the whole of the clan, as opposed to smaller lineage groups, communicate with their descendants through a tribal medium selected by them and of a different totem. His presence and services are secured by the clan by a transfer of cattle reminiscent of roora (marriage consideration).

Of course people other than clansmen and women live under the jurisdiction of the chiefs and, indeed, usually outnumber them. In the first place the wives of clansmen are required to be of other clans or sub-clans, marriage among the Shona being exogamous and, on the whole, patrilocal.

The family from which a clansman's wife comes must have a different totem or a different principal praise name from his. Marriage within the sub-clan would constitute incest (makunakuna), a sin which is offensive to the founding father and punished by him.

Clansmen belonging to clans other than that of the chief, and who live under his jurisdiction, are called vatorwa, vasokeri, or vauyi. Being outside the ruling lineage, they look to ancestral spirits of their own, either to their founding father, where their group lives in its own land, or to the nearer circle of family spirits.

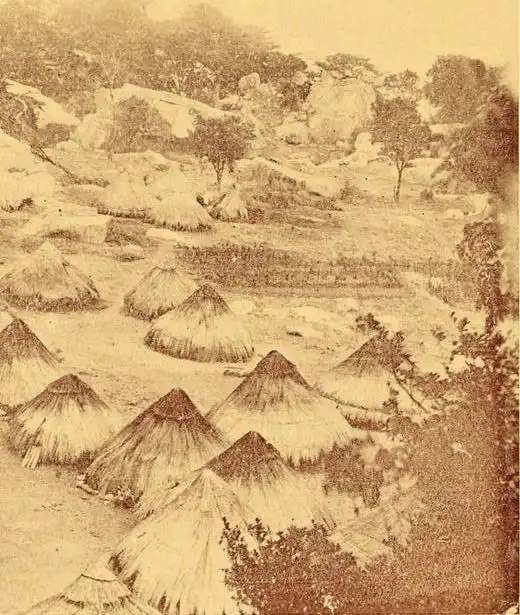

The country of the ruling lineage, if large enough, is administered by districts, each district being composed of villages, and each village of hamlets. The Shona nomenclature reflects the structure. The chief (ishe) of a territory (nyika) is called sanyika (master of the land). The administrative head of a district (dunhu), normally a kinsmen, is called sadunhu. The head of a village (musha) is called samusha or, because he keeps the tax register, sabhuku. The head of a hamlet is called samana, and a household head saimba. If vatorwa form a sufficiently numerous group, they may constitute a dunhu with a sadunhu of their own lineage. The qualification for these positions of leadership is lineal seniority in the group concerned, though disabilities of age may be a limiting factor.

The clan as a lineage group is concerned with its perpetuity and the transmission of its life. Clan praises contain references to the sexual attractiveness of its members which draws women to them, ready to become their wives. The clan praises include a special sub-genre in honor of its unmarried daughters which celebrate their attractions to potential husbands.

In such poems mention is made of the clan's founders on the female side, namely the sister of the founding father, and the sisters of successive founders of sub-clans. These women are known as zimbuya guru (great ancestress), mbonga (dedicated woman), zisarumbuya, or vamoyo.

Their names are invoked to thank them for their continued influence on the daughters of the clan, to pray for its continuance, and to recall the values for which they stand to the minds of the present generation.

The mbonga is the repository and the model of womanly qualities of which the clan desires to see its daughters possessed so that its name may be honored wherever the women go as wives. These qualities include traits of character which are mentioned among the clan praises, but also, and more important, moral and physical preparedness for married life.

In clan traditions the sikarudzi and his sister, the zimbuya guru, stand at the beginning of its life. The new clan life required the dedication of a sister to an unmarried life as a mbonga consecrated to the safeguarding of the clans's charms which enabled it to govern and administer the land, and protect it against the hazards of war, hunting, and sickness.

These charms, makona, achieved their potency from the substances which were their ingredients, and they were strengthened by an act of sexual intercourse between brother and sister.

An example of the formation of a new branch, dungwe, is recalled in the traditions of the Mutumba chieftaincy. This branch stems from that of Chihota, which itself stems from the line of Mutasa, chief of the Manyika. All three lineages have the same totem, Tembo, but the principal praise names of the two junior lines differ from that of the senior. Mutasa's chidawo is Samaita, while that of Chihota and Mutumba is Mazvimbakupa.

Tradition recalled that the leader of the Mutumba line came from the house of Chipendo. He was chosen by the elders as sikarudzi, founder of the line, when the group decided to migrate from the country of Chihota. A new mbonga had to be chosen from among the clanswomen, and the choice fell on Nyahuva, a sister of Guvamombe.

She was instructed in her duties by the mbonga of the vaHota. Guvamombe and Nyahuva had to prepare and consecrate new charms between them, kupinga makona, for the protection of the new branch. The charms reputedly consisted of various mazango, the ingredients of which were kept secret.

These were subsidiary charms, each with its own purpose, and designed to meet the different dangers which threatened the clan's life stemming from war, sickness, sterility, the hazards of hunting, and so on.

In the past the office of mbonga was a regular one in the structure of the clan. A new mbonga would be chosen from among the clanswomen to succeed to the office upon the death of her predecessor, though, during the interregnum, the duty of keeping the clan's charms would devolve upon the chief, who delegated it to his second wife, the mukaranga.

The mbonga's main tasks were the safeguarding of the clan's charms and the preparation of the young women of the clan for marriage.

The charms were kept in granaries, though, on occasion, also on the mbonga's person. One in particular, a duiker's horn in which the hwanga was kept, was always worn around her neck. This was a charm which enabled the clan to evade its enemies after a defeat by becoming invisible to them, and by opening up to them a route of escape through a fissure in the ground.

On hunting expeditions the mbonga could accompany her brothers and live at the hunting camp, musasa, with her bodyguard. She kept the hunting charm by her on these occasions. She was also responsible for keeping a drum by her side which was beaten in order to recall her brothers to the camp and tell them where it was.

The potency of the clan charms had to be renewed every new moon. This was a responsibility of the clan elders and of a sister's son or daughter, dunzvi. The diviner had no part to play in this essentially group responsibility and ritual. Certain powders and oils were required, and, of course, the blessing of the ancestors.

The mbonga was also responsible for the training of the the young women of the clan for marriage. This included both moral and physical preparation. Girls were expected to be chaste. They were subject to surveillance and periodic inspection to ensure that, when they married, their husband's clan would send back the mombe yemachiti, a token of gratitude for the new wife's upbringing and that she had been found to be a virgin.

The training also included tuition in the symbolic and culinary niceties of married life such as the preparation of kamutsa nedako, an early morning delicacy, and chinamu, another for the evening, after the men had left the dare, the village meeting place.

A new mbonga or mbonga-designate had to spend some time at the Mabwe aDziva (the Rocks of Dziva), where the shrines of Mwari are to this day. There she took her place among the vakadzi vaMwari (the wives of Mwari). As a woman dedicated to Mwari she was able to learn her role in the clan's life, particularly as it affected her responsibilities to her sisters.

The traditions mention the suffering which mbonga incurred at the hands and from the tongues of their brothers' wives, and could lead to their suicide. This was occasioned by criticism of favoritism and partiality made by mothers of girls who were jealous of others.

The mbonga were assisted in their work by women in different districts to whom could be delegated part of their responsibilities in regard to the clan's daughters. These were called zitete and to them responsibility for the clan's daughters seems to have passed today. For example, if a wife wishes to visit here zitete because she is confused or ignorant about some aspect of her wifely duty, her husband must allow her to go.

Boys and young men were also, of course, trained in the qualities expected of them. The herding groups and the dare were the training ground and forum for clan virtues and values.

Instruction in the duties of a husband was given to boys by their mother's brothers, madzisekuru, and their wives, madzimbuya. The mother's brother was also responsible for giving his nephews the medicines required for their development over puberty, mishonga yemusana (medicines for the back).

Wives at their husbands' homes always retain their own totem, although, in most groups, they are addressed by their husband's principal praise name. Thus the wife of a Tembo clansman of the Chihota chiefdoms will normally be addressed by her husband, and even by her own clans people, as Mazvimbakupa.

However, a wife always retains the support of her clansmen, especially her father and brothers, and, ideally, the bride-wealth paid to her family to secure her absorption as wife into her husband's clan is liable to forfeiture should she be forced to leave her husband through no fault of her own. This support involves, of course, the continual protection of the ancestral spirits of her clan.

The clan spirits of both husband and wife are present at the act of conjugal intercourse, and are invoked in the praises which the spouses exchange at this time. This occasion is, in a very real sense, the meeting of two clans, and demands its appropriate ritual of acknowledgment and thanks.

The proportion of lines in this poetry which deals with the spouse, compared with those which deal with his or her clan, varies from occasion to occasion, but it seems that the aspect of ancestral gift in the person of the spouse, and of ancestral help in the formation and protection of new life, is not neglected.

Likeness to a paternal grandfather will betoken a special moulding influence on his part in the very life and substance of the child. Likeness to a maternal ancestor will show that her clan spirits were particularly near at the moment of conception.

As the child grows, the interest of the spirits on both sides continues. The traditional songs used by mothers to quiet their children invoke both groups, for either may be responsible for making their wishes felt through making the babies cry.

THE FATHER'S CLAN

As a child grows and is absorbed into the clan, it learns to

group the people who surround it into classes of kin and

non-kin. Each class of person has its term of address and

response according to the relationship involved, and these

verbal exchanges are but part of the range of patterns of

manners which the child has to learn as it grows up.

Within the clan the child's relationship to clansmen differs according to generation, and these different relationships are marked by different terms. Thus the father's father is called sekuru (or sometimes tateguru), and so are all clansmen coeval with him. Coeval clanswomen are called ambuya (grandmother) as are the wives of all madzisekuru (grandfathers). The child is called muzukuru (grandchild) by all these people. The husbands of clanswomen called ambuya are vakuwasha. They call their wives's grand-nephews tezvara, and their grand-nieces, muramu.

Clansmen of the fathers generation are called baba (father), and clanswomen are called tete (or sometimes samukadzi) - paternal aunt. Their spouses are called, respectively, amai (mother) and mukuwasha (relative-in-law, usually male). Fathers and mothers call the child mwana, the paternal aunt calls it muzukuru, and the mukuwasha calls it tezvara or muramu (male or female relative-in-law)

In the child's own generation the siblings of its own sex are distinguished on the basis of age, but there is a single term for siblings of the other sex. The terms mukoma and munun'una are correlative terms for siblings of the same sex, the term hanzvadzi a mutual term between siblings of different sex.

Thus, within the clan, generations are marked by the use of special terms. The factor of sex is one which tempers the relations of respect and subordination between members. Thus relations between a father's sister, tete, and her brother's children, vazukuru, are relaxed. But those between siblings of the opposite sex, hanzvadzi, are not.

Thus kinsmen, hama, of the clan are divided into those with whom converse is relaxed and those with whom it is constrained. The former are called vasekedzani (those who joke together) and consist of members of alternate and of the same generations.

The exception is the relation between hanzvadzi (siblings of opposite sexes) the latter are vanyarikani (those who are shy of one another), and consist of members of proximate generations. The exception is the relation between children and their father's sister. Both vasekedzani and vanyarikani, however, feel bound by the ties of clan membership.

This solidarity shows itself in the ready acceptance of members of the clan, no matter where they live, and in hospitality. Responsibility for brother's children is axiomatic, for example in the provision of education and bride-wealth.

THE MOTHER'S CLAN

The child is differentially related to members of the clan

into which it is born though they share the same blood. This

is due mainly to the relations of authority and subordination

between members of parental and filial generations. In regard

to its mother's clan the child has only two relations,

distinguished by sex. The men of the mother's clan are all

called sekuru, and the women are called

amai.

Dealings between children and their mother's male kin, particularly the mother's own brothers, is relaxed and intimate. These madzisekuru call their sister's or daughter's children by the same term as the paternal grandfather and the the paternal aunts do, namely, vazukuru.

Maternal uncles and sister's children are vasekedzani, even more than in the relaxed relations of the paternal kin, since the mother's clan represents love and indulgence without authority and the need for subordination and solidarity due to clan interests.

Children call their mother's clanswomen amai. They are vanyarikani since they share to some extent the responsible relation of their sister to her children. Seniority within the mother's generation is as marked as it is in the father's. Mothers senior to the child's own mother are mai guru (senior mother) and the juniors are called mai nini (junior mother).

The simplicity of the relations between children and the members of their mother's clan, as reflected in the use of only two terms, seems to indicate that clans are seen by outsiders as unitary. Relation to one member of a clan involves relations with all members. In the relations with members of other clans sex is a far more important differentiating factor than age or generation.

Fathers' sisters and mothers' brothers play hardly less vital a part in the education of their brothers'and sisters' children than do fathers and mothers themselves. A sekuru is at home in the village of his muzukuru. The muzukuru also enjoys much freedom at his sekuru's village.

He may help himself to his sekuru's clothes and, in jest, threaten to run away with his wife who is his ambuya. He relies on his sekuru and tete for help in courtship, and for advice on sexual matters and married life. Similarly the tete is the normal confidant and chaperone for a girl in matters concerning her marriage.

The sekuru and tete are entitled and obliged to reprimand their nephews and nieces, and this may involve detailed comment on their loose behavior if it exists, in a way which would be improper and undignified for parents to do. The sekuru plays a highly important part in the education and correction of the children in a friendly and jocular way. He may take the part of the children against their parents and they value his friendship and feel confident and welcome at his home.

THE SPOUSE'S CLAN

A man is related in two ways to the members of his wife's

clan. All her kinsmen are called tezvara by him, the

term applying particularly to her own father and brothers. Her

clanswomen, particularly her own sisters, are varamu,

a mutual term.

A man's madzitezvara (kinsmen-in-law) are vanyarikani, a relationship which extends to his wife's own mother, vambuya. All these relatives call him mukuwasha. A man's relations with his wife's kinswomen are easy and relaxed, and they use a reciprocal term to one another, muramu.

A woman is somewhat differently related to her husband's kin. His fathers are called tezvara by her, and his mothers and sisters vamwene. They call her muroora. They are vanyarikani to her especially the husband's own father and mother. His brothers, however, are vasekedzani, and the reciprocal term muramu is used between them.

His children are her vana and they call her amai. His grandparents are her sekuru and ambuya, and they call her muzukuru. Thus a wife is deferentially involved in the internal relations of her husband's clan much more than he is in those of his wife, at least as far as kinship terminology is concerned.

In the village community the child finds people of other clans who are not related to him. His relationship with these vatorwa is polite, somewhat between shyness and familiarity. Among them he will find his shamwari, friends of his own sex, his girlfriends, and probably, his eventual marriage partner.

Marriage between neighbors who knew each other, vematongo, was favored over marriage with strangers. These relationships bring with them, of course, their own more familiar forms of speech.

The most familiar and unrestrained relation in Shona life are those between madzisahwira (priviledged joking friends). There is not the same freedom of choice within this relation as within the relation of ushamwari (friendship) since it is primarily a relation between clans before becoming, in particular cases, a relation between persons.

The most concrete service which a sahwira renders is to bury a co-sahwira, but this service is preceded during life by a very uninhibited and jocular relation.

It is reflected in a number of poems in this collection. Because madzisahwira may take extreme liberties with one another, their services are available to other people should there be a need to convey criticism or a desire for reconciliation, a need to ask a favor, or make known a grievance to a partner in the joking relation.

This sahwira is allowed and expected to be direct and pointed in his criticism of the behavior of his co-sahwira, and the latter may not take offense.